What can we learn from the Japanese fit note?

Last week, I spoke to Dr Yusuke Noguchi, Occupational Health Physician in Japan who drove the policy behind the introduction of the fit note in Japan. Here are some highlights from our conversation comparing the challenges each country is facing in the work and health space.

LS: In the UK, the spotlight is currently on the fit note as we are concerned that more of the working age population is becoming economically inactive due to ill health. The fit note, if used effectively, could help support people keep in work while living through a period of ill health. How does this compare to what is happening with the labour force in Japan?

YN: In Japan we are also concerned about a labour force shortage, primarily because of an aging population and declining birth rate. This is part of why the fit note was introduced around four years ago, with the idea of keeping people in work where possible.

LS: That’s interesting, so the fit note is a relatively new addition to the work and health landscape in Japan?

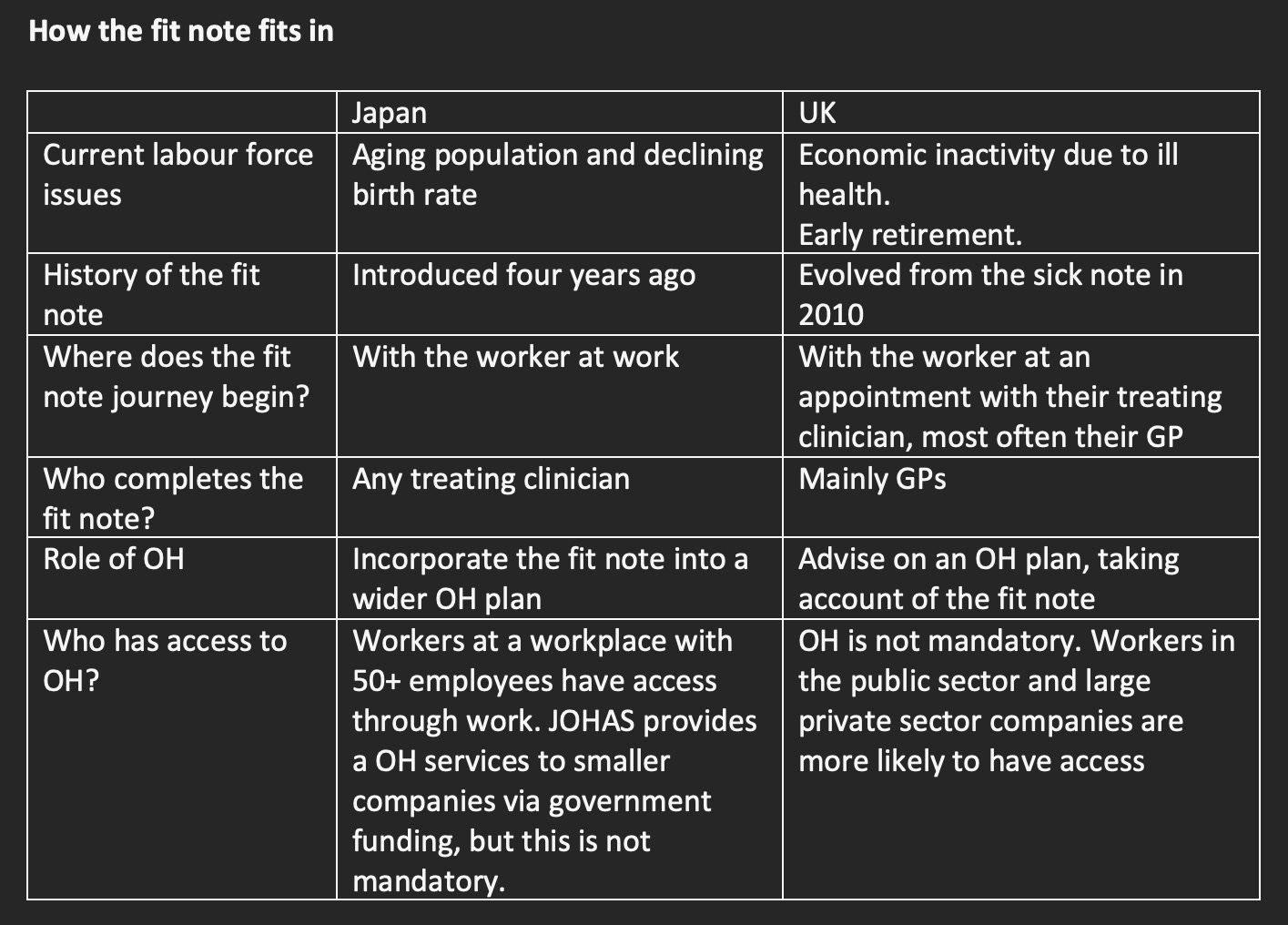

YN: Yes. In Japan, companies with 50 or more employees need occupational health physicians. But, in general dialogue between OH clinicians and treating teams around work and health was limited. Introducing the fit note has also helped open up dialogue between worker, employer, OH clinicians and treating teams.

LS: The fit note could be a great tool to open dialogue around work and health but in general there is limited communication between the different stakeholders in practice when we use the fit note in the UK. How do you achieve dialogue between stakeholders via the fit note in Japan?

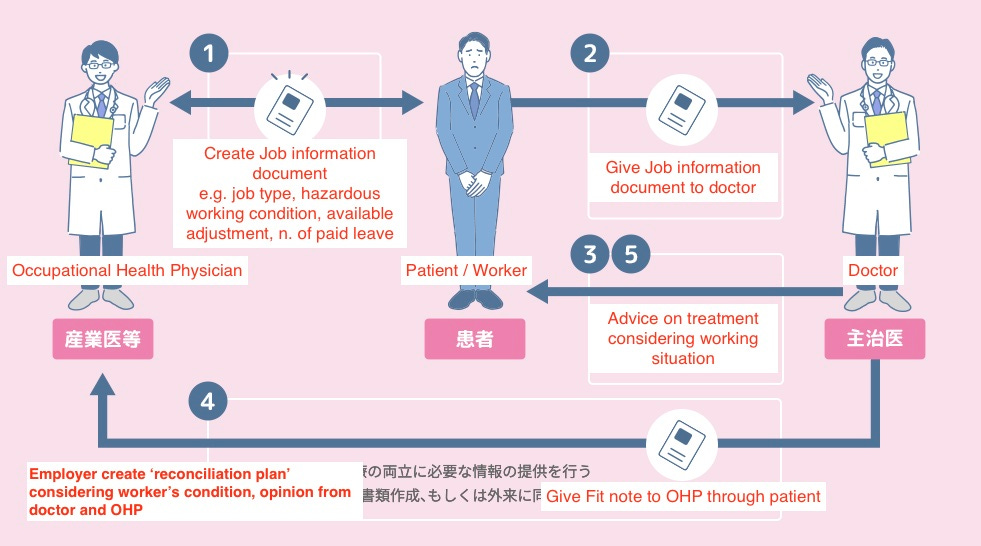

YN: The worker is at the centre of the model. The fit note starts with the worker providing some information about their job to their treating team. They take this to their treating clinician who assesses them with the aim of putting their health and function in context of their job, suggesting some general recommendations. The worker takes this to their occupational health department for support with refining this into an occupational health plan. The occupational health clinician communicates with the worker’s manager to action the plan.

LS: So the fit note journey starts in the workplace, not at a doctor’s consultation? That is a great idea since one of the issues we face in the UK is treating clinicians being unfamiliar with the worker’s job and working conditions.

YN: Yes, we learned that through experience. Originally the journey began with the worker consulting with the treating clinician but the government found the quality of fit notes was poor because treating clinicians did not have a good understanding of their patient’s job. We changed the model in response to this in 2020, and since then starting the journey at the workplace has improved use of the fit note.

LS: I can see how that would work well, because the worker engages with the whole process. The starting point is the worker thinking about their role and how it maps to their function with a view to how adaptations could help them. In contrast, in the UK, workers rarely realise that adaptations are an option when they present to their GP asking for a fit note. They view it as a ‘sick note’ with a binary outcome. This can make managing expectations and shared decision making challenging in a short GP consultation. What challenges have you faced implementing this model in Japan?

YN: Lots of workplaces have been promoting use of the fit note, so workers are more aware of it and are willing to engage with the process. The main challenge has been around onboarding the treating clinicians so they are able and willing to fill out the fit note. The majority of treating clinicians are not confident about providing advice on patients’ work. Another challenge has been around worker access to OH once they have a completed fit note.

LS: Those challenges are familiar to us In the UK. OH is not a speciality that gets much airtime in undergraduate or postgraduate training so non OH clinicians can feel under-qualified to advise on work and health.

YN: We have that challenge too. This is being addressed though. The Japan Medical Association is offering OH training for physicians across specialities. Around 1/3 of physicians have now had some training in OH. In addition, the government has published guidelines and manuals for clinicians.

LS: So the Japan Medical Association is encouraging a range of clinicians to upskill in OH so they can apply this training within their own speciality. We also have a route to OH training for doctors outside of OH speciality training, the Diploma in Occupational Medicine. However, there remain barriers to doctors deploying these skills within their specialty. I still find it hard to make the most of the fit note in a GP setting and one of my main obstacles is consultation time. Most workers don’t have access to OH through work so the fit note is an important backstop.

YS: The Japan Organisation of Occupational Health and Safety (JOHAS) provides OH services to companies without OH specialists. JOHAS’s specialists communicate with the worker and their manager, and support creating the OH plan. JOHAS is funded by the government and companies can use their service for free. But it is not mandatory. Just like in the UK, finding a way of supporting workers without access to OH is a big issue in Japan.